Are private schools still worth it?

With VAT and quotas on university places, it is a vexing and valid query. We try and answer it.

Seven percent of children in the UK attend private schools. That is over a half a million children. With a rising cost of living and the implementation of VAT (sales) taxes on these schools, many parents are asking themselves is this worth it? It is a complicated question.

The question becomes even more relevant when considering the goal. For many it is about a path to a reputable university. In an effort to support less privileged students, universities have announced efforts to take in more children from non-fee paying schools. The open letters from heads of prestigious fee paying schools decrying the quota systems applied to students from elite schools reflects concern in the private school parental community.

And when you look at the AI generated image above, you would think why not tax these schools more? However, more often than not, AI is representative of the cliche view on an issue - that algorithm sifts through available material to compose it’s representation. Doubtless, that image above, created by ChatGPT, is similar to that conjured up in the minds of millions of voters, when they think of a private school.

For most middle class voters though, fee-paying schools are far less glamorous. They are a sacrifice made to give their children a better start. And the real question is do parents choose a school or do schools choose the parents. And this leads to the first secret of private schools - the confusion on causation and correlation. However, first let’s set out a crude topography of the world of private schools.

Not all private schools are the same

One important caveat is that not all private schools are the same. There are rankings that list schools by their academic performance, and those in the top set (top 20) likely prize academic achievement more than the rest.

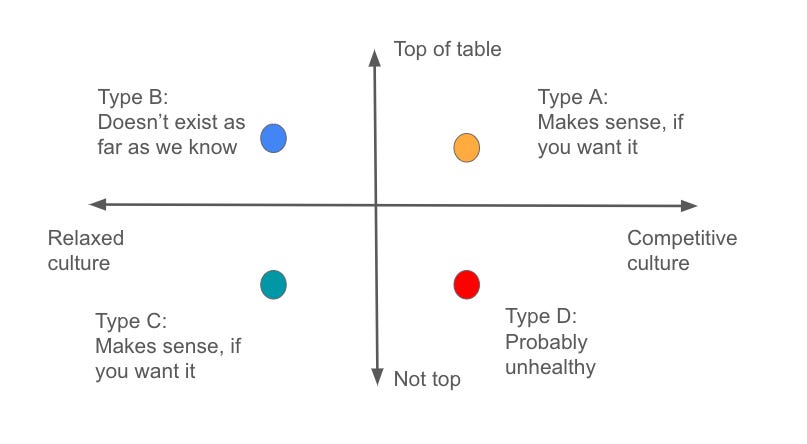

So we have created a chart above for you to think about the type of school that exists, in the private space, but also more generally.

Type A above are the elite schools. Top of the academic tables, often with the most students going to the next preferred destination (elite university, etc), and very challenging to gain entry to. They have a competitive culture, attract the right type of students (and associated competitive parents - see article here) and produce great results.

Type B is a unicorn - we don’t know any that exist. They produce great results, with a relaxed culture. Perhaps that is where technology comes in. That said with technology, individuals like Elon Musk want to set up schools that have a material improvement on the current system - may be they will get us to that utopia.

Type C is the rest of the pack. They are not competitive schools, and often do not want to be. They prioritise nurture over competition, and openly say so. Languishing in the league tables doesn’t really bother them, for it is all about the child’s welfare and growth. This could be compared to systems on the continent. The Finnish education system famously doesn’t start until the age of seven, and yet for sometime enjoy the position at the top of Europe. I.e. it is nurturing, with a view that children can flourish later.

Type D sadly does exist. It is often a Type C school trying to become a Type A. And so those schools are trying to climb the league tables, may not have discovered the secret sauce of success yet, and so have the toxic combination of a competitive culture without the results.

With that crude taxonomy out of the way, let’s keep investigating.

Elite Private schools choose their parents

So we have established that private schools vary significantly. Now to the juicy detail. One could be forgiven for concluding that selective private schools choose parents, rather than the academic merit of their respective child. This is particularly obvious when it comes to assessments for younger children. It is impossible to assess a child at the age of four (and arguably even seven), and predict their academic success at eighteen.

This means that selective schools are also likely to be assessing parents. Will parents prioritise academic success? If they do, the chances are they are less likely to accept poor exam results, and so the private school and the parent now have their objectives aligned.

After all, given that parents apply to top schools based on the school’s position in exam results’ tables, and the exits from that school to major universities, it makes sense for private schools to want parents who will push their children to gain top grades - it is a circular, and mutually beneficial relationship.

And those metrics apply all the way down the chain. Pre-prep schools publish their list of exits to prep-schools, and so on. Parents select schools on performance metrics, but the schools also select parents, who help them achieve those metrics.

And so it is plausible that academic success is more correlation - that had you put those parents, and their children anywhere, they would still perform academically. I.e. they are parents who will pull out the stops to curtail any downturn in academic performance - it is one of their major objectives.

The competitive virtuous cycle

However, that is not entirely fair on private schools. Whether the schools realise it or not, they are creating a cauldron of competitive parents - and that has a potency of its own. I.e. there is a process, that selects children based on a competitive assessment, draws in the parents who are academically ambitious for their child, and then the schools often promote competition internally, via tables or competitions.

That creates an environment for further internal (and external, in intra-school competitions), rivalry, that given the group of parents involved, results in higher performance. The magnitude of this cycle, depends on the school, its culture and the specific cohort of parents.

This is likely most applicable to the elite schools. The further down the school is on the tables of academic performance, the more relaxed the culture is likely to be.

What value does a private school add?

Once it becomes clear that it is parents, not schools, that are more likely to determine the academic success of the child, the natural response may be to spurn private schools. Not so fast.

There are of course the perks represented in the prospectus - smaller classrooms, they have the luxury of attracting the staff they want, better facilities, etc: those are all valuable, but are they worth the hefty, now increased, fees?

There is likely one final intangible factor that may be more useful to parents, than all of the above, and that is the peer group. Going back a few decades, elite private schools were about networking. Access to those schools was a form of social climbing, and of course the representation of the alumni of these schools in the top seats of boardrooms to Parliament speaks volumes.

The dark side of that was the reputation it garnered as an ‘old boys network’, closed to outsiders, spurning merit in favour of familiarity and the old school tie. However, whilst this was likely a very material factor in parents’ consideration, particularly for a subset of the most elite boarding schools, it is not clear that it has the same value today.

Networks have changed. Social media and the internet has altered how people can network, and build status amongst social groups. Of course, it may not replace having a good friend from childhood, who happens to be very successful in their field, just a call away - but today most of the people you need are an e-mail or a direct message away, and if you can demonstrate value to them, they will likely engage with you - private schools (and elite universities) don’t hold the monopoly on networks any more.

However, there is a second, perhaps more important factor to peers, and it comes back to the cohort. It is difficult for parents to help young children think in abstract terms. The idea that in some other room, somewhere else, are children working hard, doesn’t make sense children under 11 - or doesn’t matter. And after 11, they can become more independent - a.k.a. rebellious.

By being in a private school, kids who tend to be naturally competitive, can observe their peers live, and in real time. This effect lasts throughout their academic life, and likely into adulthood. I.e. by being with a group of high performing kids, you are more likely to be one too, and that effect carries through to adulthood. That is perhaps the most valuable aspect of private schools.

The question for parents is ‘are the fees worth it?’, and that entirely depends on circumstances.

What are your goals?

So the picture is complicated. The prospectus is nice (there are more facilities, and smaller classrooms); it used to be about networks, though that may be accessible using alternative means; though the peer group has its own benefits of promoting performance.

To see where this fits into your long-term goals, we have to step back and take a look at the problem holistically.

The final answer is of course that it depends on your circumstances. However, here’s our take on how to think about the problem.

Let’s start with the goal. The goal is to provide a brighter future for your child. We live in an age where that is incredibly difficult to plan for. The changes in geopolitics and technology make the future less certain that it has ever been.

Our analogy for this is imagine planning for the future, living in Britain in the early 1800s. The agricultural society would transform to industrial and by the 1900s to cate for the middle class that emerged. Many of the private schools today were born in that window - when the nouveau riche and the emerging middle class sought education and status to join the traditional landed aristocracy that dominated British Society since the Norman Conquest.

It would be impossible to plan for that future in the 1800s. Similarly today with AI, Robotics, Quantum Computing, flying cars, space travel and Virtual Reality, the shape of the future is, at best blurry, or perhaps completely opaque. With the rise of China and India the geographic and commercial centres of the world are also changing or diversifying. So how does one prepare?

The skills of the future

Well the answer, we think, lies in innate skills. The capacity to think and to be resourceful. However, first and foremost, the capacity to think.

(To read the rest of the article either (a) take up a paid subscription, (b) sign up to the Creative Writing Bootcamp and receive a free subscription).